Chris Padilla/Blog

My passion project! Posts spanning music, art, software, books, and more. Equal parts journal, sketchbook, mixtape, dev diary, and commonplace book.

- Less overhead structurally

- Less complex to write and manage

- Threads in other language are more expensive as far as memory used compared to Go

- /blog

- /blog/[tag]

- /blog/[tag]/[page]

Someday My Prince Will Come - Churchill

🐉 🏰 🌌

Reefapalooza!

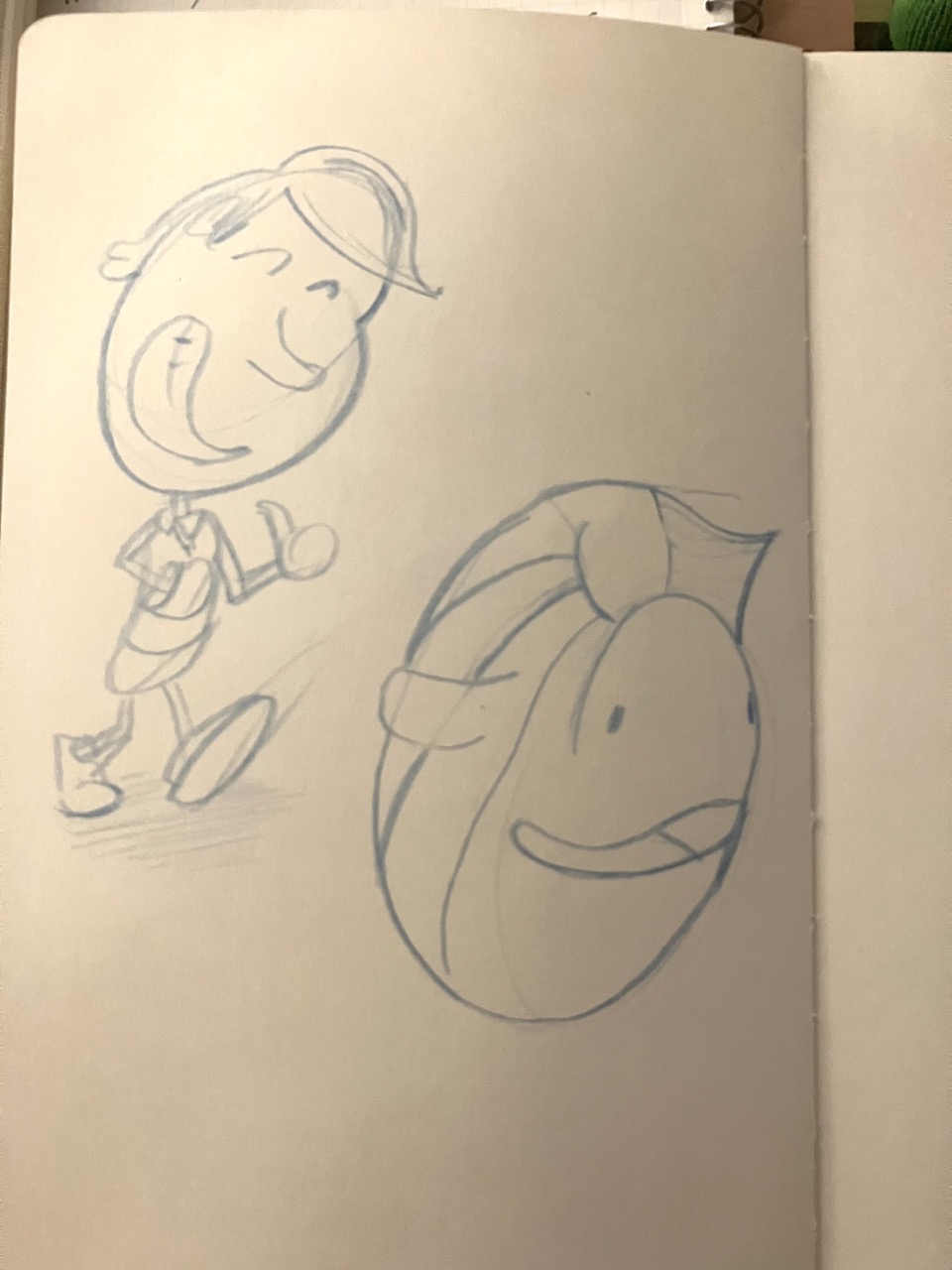

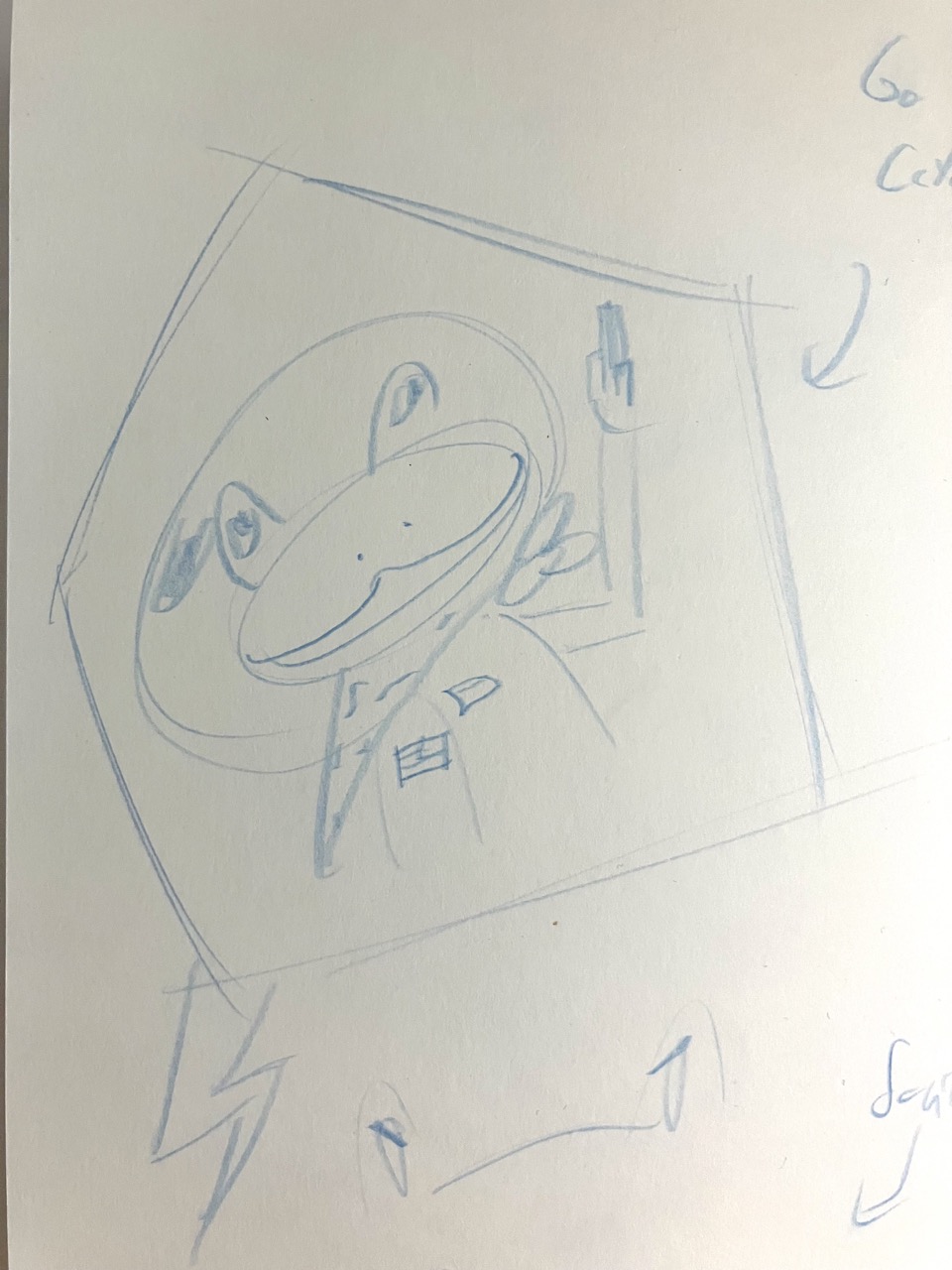

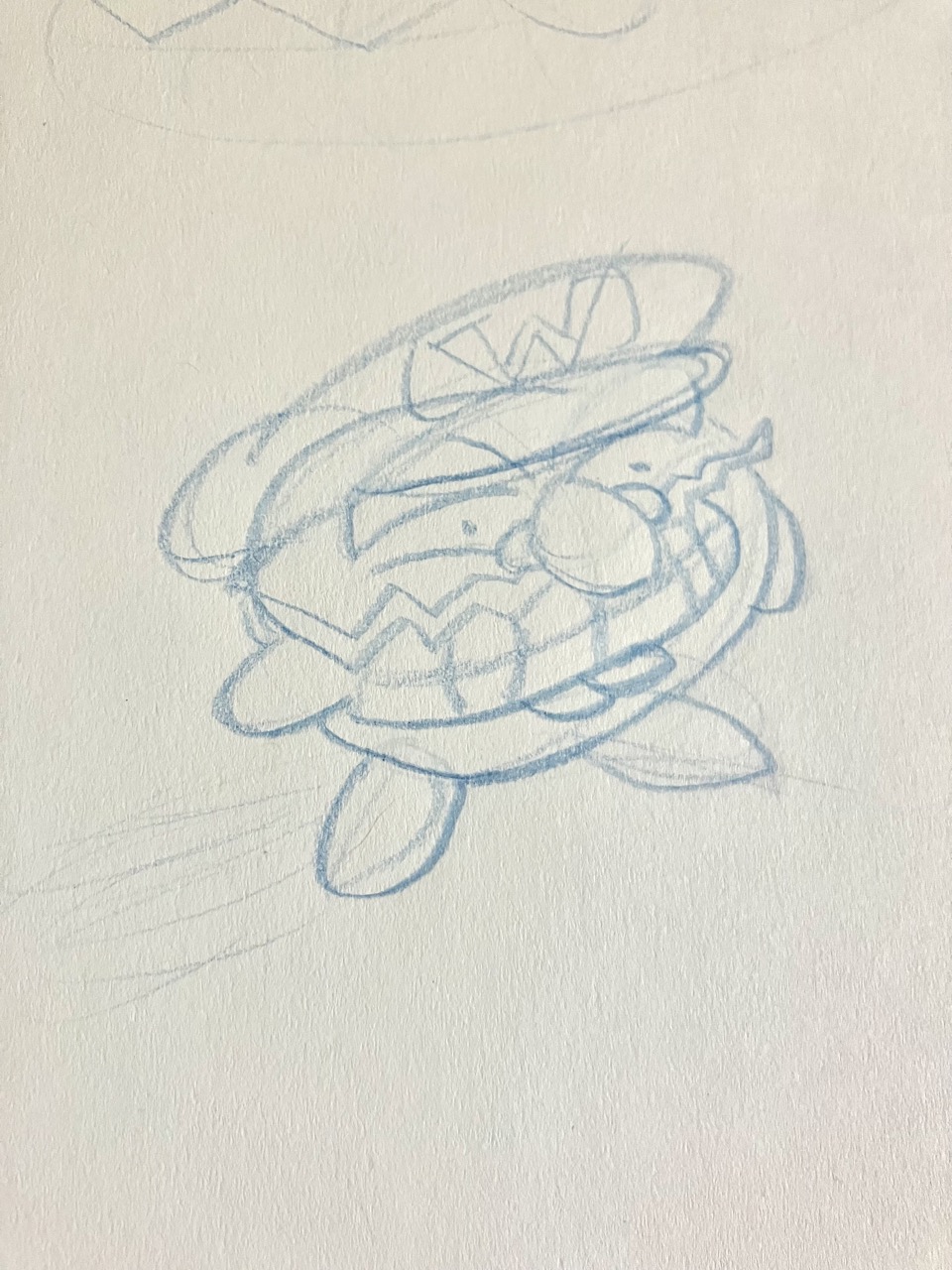

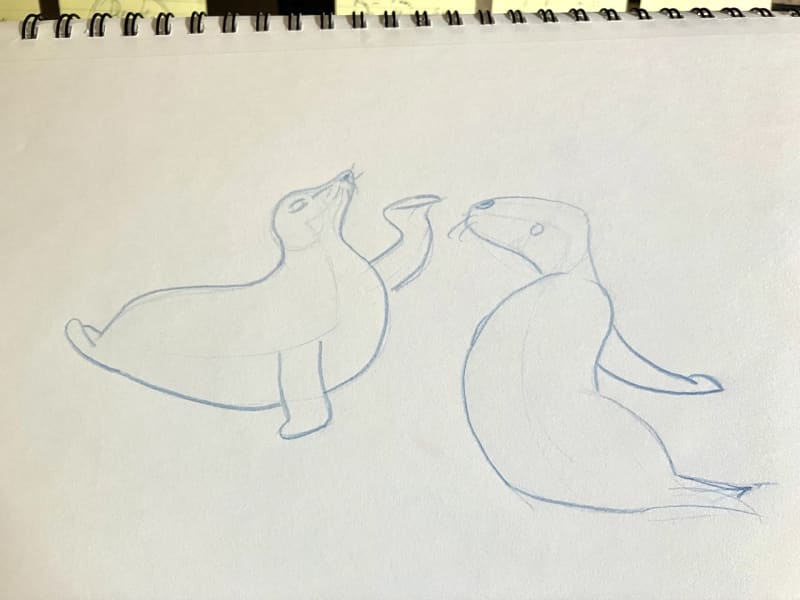

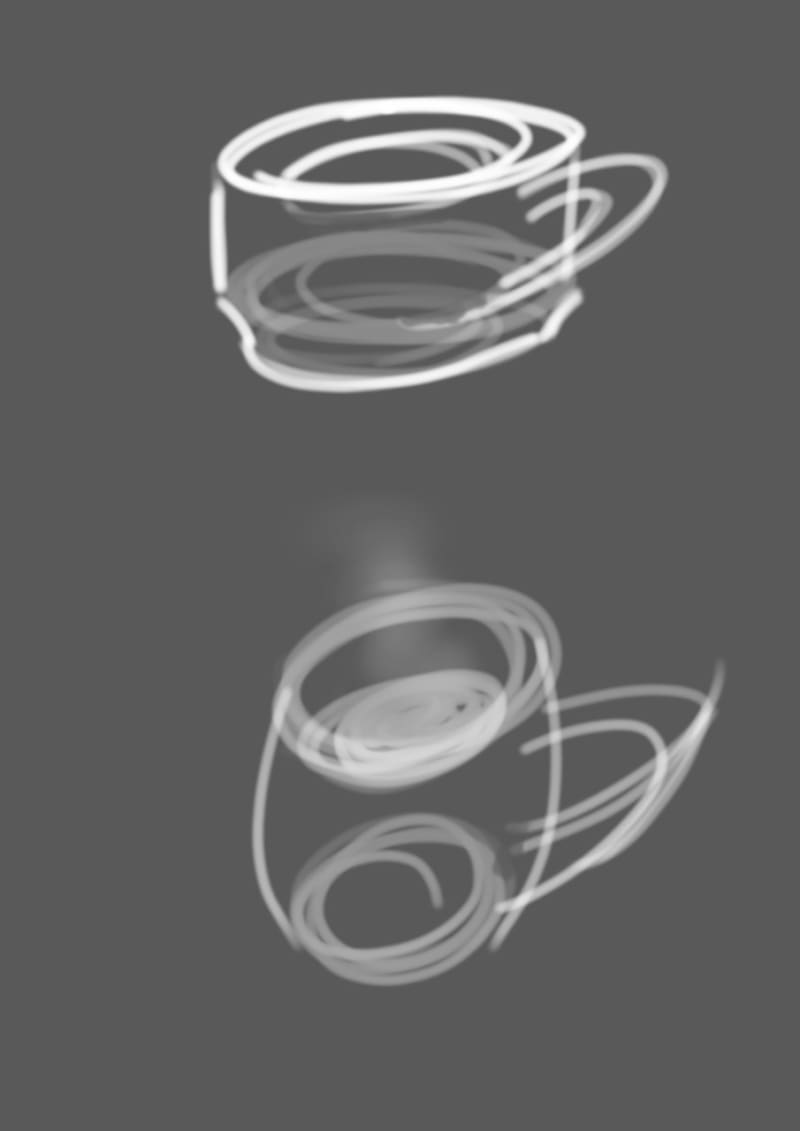

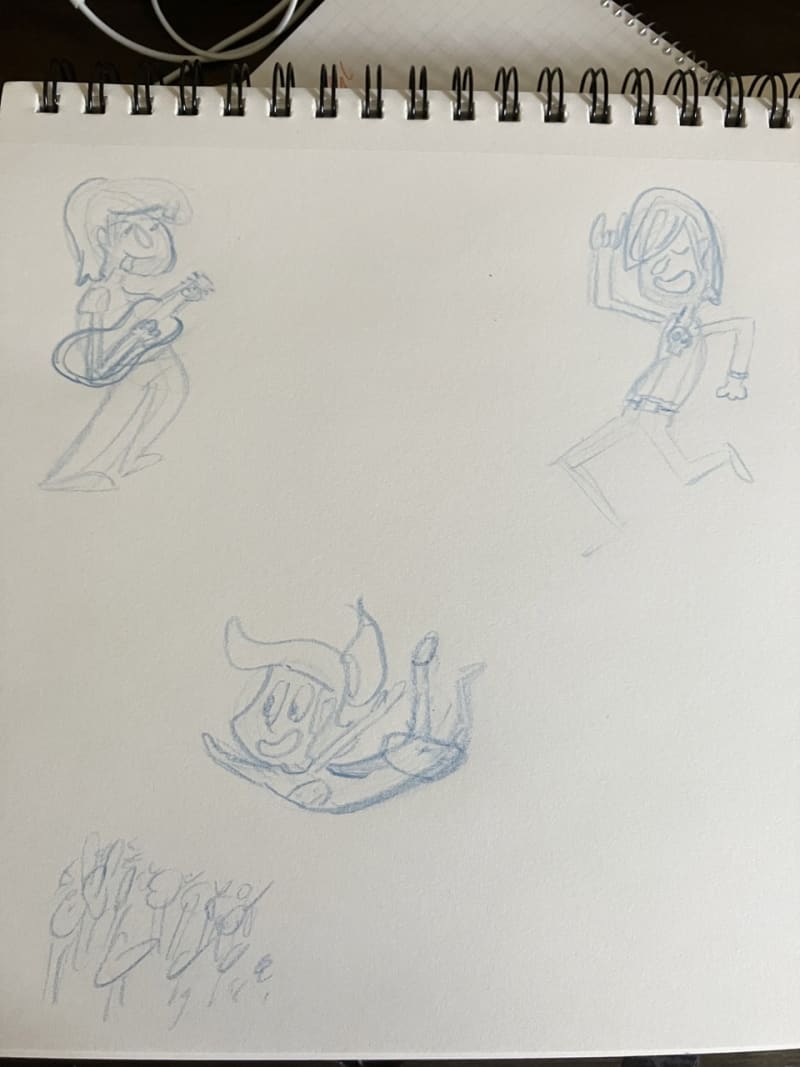

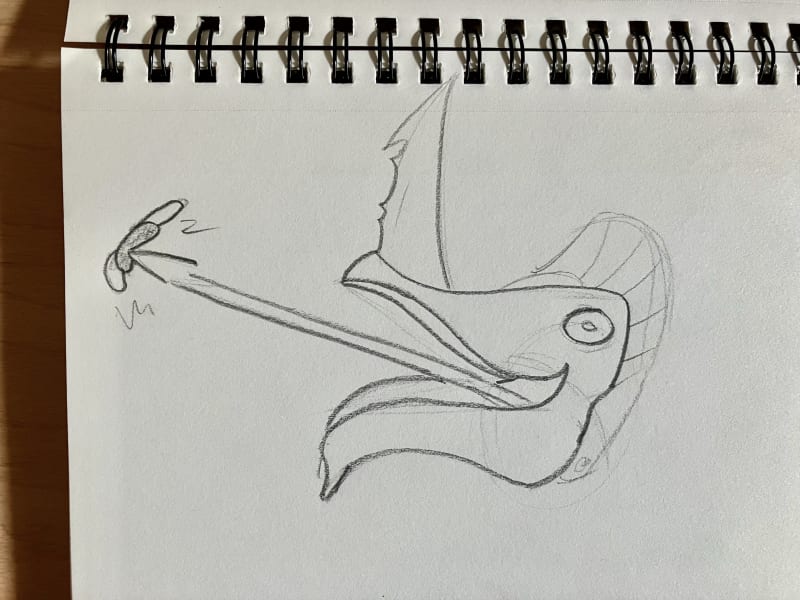

Sketches from this week!

Went to Reef-a-palooza with my folks this last weekend! Like anime conventions, but for coral and clownfish (and there was a cosplayer!)

Started watching an MST3K classic — Cave Dwellers!

Still doing loads of gestures. This new-fangled digital pen takes some wrangling!

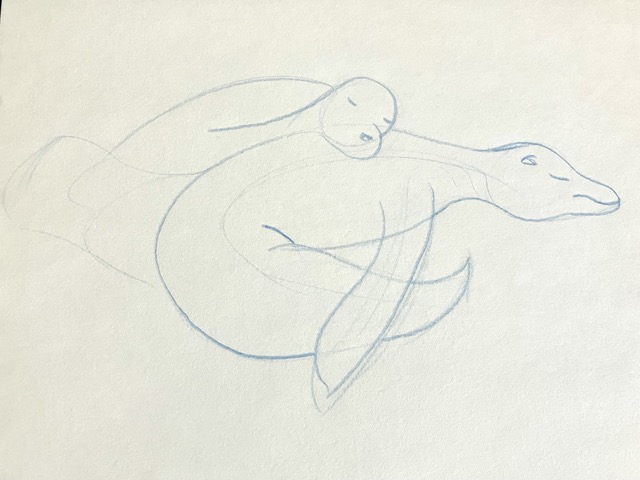

And, lastly, I'm braving my own album art illustration! This guy will be making an appearance:

Goroutines, Structs, and Pointers in Go

A potpourri of Go features I dove into this week!

Structs

Last week I looked at the Maps data type. It works similar to a JS Object, except all values must be the same type.

Structs in Go are a data structure for saving mixed Data Type values. Here's what they look like:

// Type Declaration

type UserData struct {

firstName string

lastName string

email string

numberOfTickets uint

}

// Can then be used in array or slice

var sales = make([]UserData, 0)

var userData = UserData {

firstName: "Chris",

lastName: "Padilla,

email: "hey@chris.com",

numberOfTickets: 2,

}

// accessing values:

booking.firstName

// in a map, you would use bracket syntax

// booking["firstName"]This is comparable to a lightweight class in languages like Java and C#. And, of course, the type declaration will look familiar to any TypeScript users.

Goroutines

This is what I've been waiting for!

Goroutines are the key ingredient for Go's main benefit: Lightweight and easy to use concurrency.

The strengths of Go over other languages:

Goroutines are an abstraction of an actual OS thread. They're cheaper and lightweight, meaning you can run hundreds of thousands or even millions without affecting the performance of your application.

Java uses OS threads, takes a longer startup time. Additionally, those threads don't have an easy means of communicating with each other. That's made possible through channels in Go, a topic for another day!

Sample Code

The syntax for firing off a concurrent function is pretty simple:

// Do something expensive and Block the thred

sendTickets()

// Now try this non-blocking approach, creating a second goroutine

go sendTickets()There's a bit of extra work needed to align the separate Goroutine with your main function. If the above code was all that was in our program, the execution would exit before the result from sendTickets() was reached.

Go includes sync in it's standard library to help with this:

import (

"sync"

"time"

)

var wg = sync.WaitGroup{}

wg.Add(1)

go sendTickets()

wg.Wait()

func sendTickets() {

// Do something that takes a while.

wg.Done()

}When we create a Wait Group, we're essentially creating a counter that will keep track of how many concurrent methods have fired. We add to that counter before starting the routine with wg.Add(1) and then note when we want to hold for those goroutines to end with wg.Wait()

Already, with this, interesting possibilities are now available! Just like in JavaScript, you can set up a Promise.all() situation on the server to send off multiple requests and wait for them all to return.

Pointers

Pointers are the address in memory of a variable. Pointers are used to reduce memory usage and increase performance.

The main use case is in passing large variables to functions. Just like in JavaScript, when you pass an argument to a function, a copy is made that is then used within that function. If you were to pass the pointer instead here, that would be far less strain on the app's memory

func bookTickets(largeTicketObject TicketObj) string {

// Do stuff with this large object

return "All set!"

}Also, if we made changes to this object and wanted the side effect of adjusting that object outside the function, they wouldn't take effect. We could make those changes with pointers, though.

To store the pointer in a var, prepend & to the variable name:

x := 5

xPointer = &x

fmt.Println(xPointer)

// Set val through pointer

*xPointer = 64

fmt.Println(i) // 64Faber - Fantasia Con Spirito

Spooky music month! This one feels very "Cave of Wonders" from Aladdin. 🧞♂️

Jet Set Radio Vibes

I give one listen to the Jet Set Radio Soundtrack, and now I get some funny 90s hip hop inspired ditties in my recomendations. Not bad!

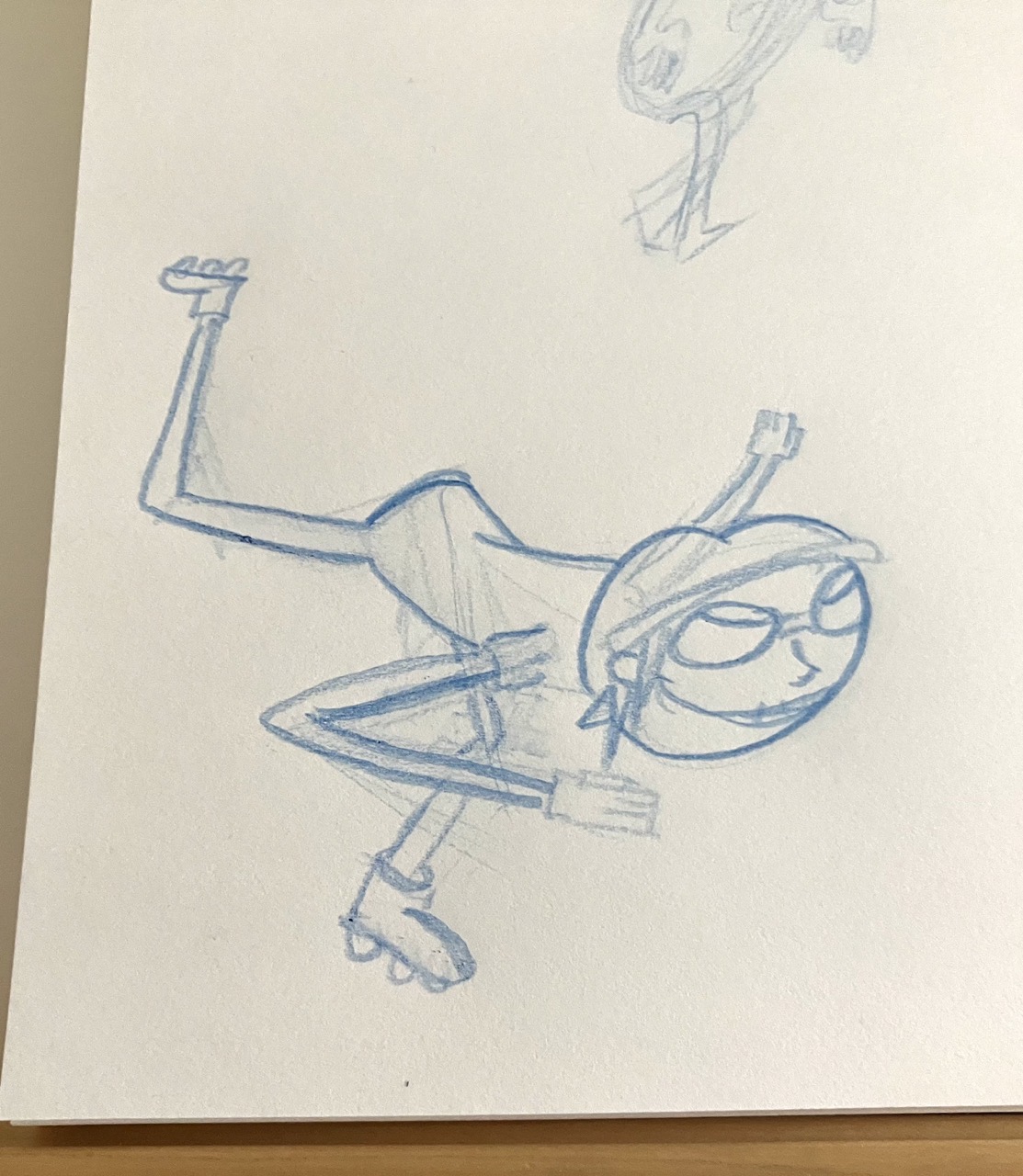

Been doing lots of gesture drawing digitally to help get used to the pen. It's a surprising jump from traditional to wacom!

Lastly, I'm sorry to say that Anthony Clark bore the horrible news: #Warioctober has arrived.

I regret to inform you that today is the beginning of #Warioctober , where everyone, be they just or wicked, must honor the terrible creature Wario. Here is Classic Wario. May we be forgiven for what we must do. pic.twitter.com/i99DQTjToR

— Anthony Clark (@nedroid) October 1, 2023

I've tried to escape it, but the punishment for skipping out is much more fowl than the ritual itself.

Tourist's Guide to Go

I'm dipping my toes into Go! I became interested after hearing about how accessible it makes multi-threaded logic to coordinate, especially on cloud platforms.

I've been there with JavaScript and Python: it could be handly for processes running in tandem having the ability to communicate. Seems like Go opens this communication channel in a way that's easier to manage than a language such as Java. (All from hearsay, since I've not dabbled in Java just yet.)

I'm excited to dig into all that! But, as one does, first I'm relearning how string templating works in the new language:

Compile Time Errors

When getting ready to run a main.go file, checks will be made to ensure there aren't any procedural errors. Go checks for unused variables, ensures types match, and that there are no syntax errors. A nice feature for a server side language, keeping the feedback loop tight!

Static Typing

Like C# and Java, Go is statically typed. On declaration, variables need to be assigned a type.

var numberOfCats uintWhen assigning, the type can be inferred:

const conferenceTickets = 50Variables

Constants and mutable variables exist here. Somewhat like JavaScript, the const keyword works, and var functions similarly to how it does in JavaScript. No let option here.

A shorthand for declaring var is with := :

validEmail := strings.Contains(email, "@")This does not work with the const keyword, though.

Slices and Arrays

Arrays, similar to how they work in lower level languages, must have a set length defined on declaration:

var bookings [50]stringSlices, however, are a datatype built on top of Arrays that allow for flexibility.

var names []stringBoth require that all elements be of the same type, hence the string type following [].

Maps

Maps in Go are synonymous with Dictionaries in Python and Objects in JavaScript. Assigning properties can be done with the angle bracket syntax:

newUser := make(map[string]string)

newUser["firstName"] = userName

newUser["email"] = email

newUser["tickets"] = strconv.FormatUint(uint64(userTickets), 10)Maps can be declared with the make function:

newUser := make(map[string]string)For Loops

There's only one kind of For loop in Go. Syntactically, it looks similar to Python where you provide a range from a list to loop through:

for _, value := range bookings {

names := strings.Fields(value)

firstName := names[0]

firstNames = append(firstNames, firstName)

}Range here is returning an index and a value. Go will normally error out if there are unused variables. So to denote an intentional skip of the index property, the underscore _ will signal to go that we're ignoring this one.

Package

Like C# Namespaces, files in go can be grouped together as a package. You can do so with the package keyword at the top of the file:

package main

import (

"pet-app/cats"

"fmt"

"strconv"

"strings"

)

func main() {...}Notice "pet-app/cats": here we can import our packages within the same directory with this syntax. "pet-app" is the app name in the generated "go.mod" file, and "cats" is the package name.

Public and Private Functions

By default, functions are scoped to the file. To make it public, use a capital letter in your function name so it may be used when imported:

func BookTickets(name string) string {

// Logic here

return res

}Parkening - Spanish Dance

Seals EVERYWHERE!!

Migrating Blog Previews from SSR to SSG in Next

I've re-thought how I'm rendering my blog pages.

When I developed the site initially, I wasn't too worried about the difference between SSR and SSG. If anything, I wanted to lean on server rendering blog content so scheduled posts would load after their posting time passed.

Since then, my workflow has changed over to always publishing posts when I push the changes to GitHub. Posts are markdown files that are saved in the same repo as this site, so anytime a new post goes up, the site is rebuilt.

All that to say that I've been missing out on a juicy optimization opportunity with Next's static page generation!

So it's just as easy as switching the function name from getServerSideProps over to getStaticProps, right? Not quite in my case!

Page Structure

The pages that I'm looking to switch over are my blog feed pages. So that includes:

/blog is easy enough!

/blog/[tag] is the landing page for any of that tags clicked on either in a post or on my homepage. Tags could be what I have listed as "primary tags" such as "music", "art", or "tech." They could also be smaller tags, such as "React" that I have linked on individual blog pages, but that I don't list on my landing page or blog index page.

Some of those tags are now rendering content through pagination! So I have to take into account [page] numbers as well.

To get the full benefit of Static rendering with dynamic routes, I'll have to provide the routes that I want generated. Next has a fallback to server render requests that don't have a static page, so I'll exclude my smaller tags and focus in on the primary tags. I'll also want to generate the paginated links, measure how many pages need to be rendered per tag.

getStaticPaths

getStaticPaths is the function where I'll be passing in my routes. This is added outside of the component alongside getStaticProps to then generate the content for those routes.

For Tags Rendered as a List Page

This is pretty straightforward for tag pages. Just one level of looping involved:

export async function getStaticPaths() {

return {

paths: getBlogTagParams(),

fallback: 'blocking',

};

}

const getBlogTagParams = () => {

const tagsDisplayedAsList = ['books', 'notes', 'tech', 'art', 'music'];

return tagsDisplayedAsList.map((tag) => {

return {

params: {

tag,

},

};

});

};For Paginated Tags

For music and art, it's one more level of looping and a few more lines of code:

export async function getStaticPaths() {

return {

paths: getBlogPageParams(),

fallback: 'blocking',

};

}

const getBlogPageParams = () => {

const allPostFields = ['title', 'date', 'hidden', 'tags'];

const allPosts = getAllPosts(allPostFields);

const publishedPosts = allPosts.filter(filterBlogPosts);

const res = [];

const fullPostPreviewTags = ['art', 'music'];

fullPostPreviewTags.forEach((tag) => {

const capitalizedTag = capitalizeFirstLetter(tag);

const regex = new RegExp(capitalizedTag, 'i');

let thisTagsPosts = publishedPosts.filter((post) =>

post.tags.some((e) => regex.test(e))

);

const count = thisTagsPosts.length;

const lastPage = Math.ceil(count / 5);

const pageNumbers = Array.from({ length: lastPage }, (_, i) =>

(i + 1).toString()

);

const tagSlug = lowercaseFirstLetter(tag);

const thisTagAndPageParams = pageNumbers.map((pageNum) => ({

params: {

tag: tagSlug,

page: pageNum,

},

}));

res.push(...thisTagAndPageParams);

});

const feedCount = publishedPosts.length;

const feedLastPage = Math.ceil(feedCount / 5);

const feedPageNumbers = Array.from({ length: feedLastPage }, (_, i) =>

(i + 1).toString()

);

const feedTagAndPageParams = feedPageNumbers.map((pageNum) => ({

params: {

tag: 'feed',

page: pageNum,

},

}));

res.push(...feedTagAndPageParams);

return res;

};There's a fair amount of data massaging in there. The key point of note is that for each tag, I'm calculating the number of pages by dividing total posts by how many are rendered to each page:

const count = thisTagsPosts.length;

const lastPage = Math.ceil(count / 5);

const pageNumbers = Array.from({ length: lastPage }, (_, i) =>

(i + 1).toString()

);From there, then it's a matter of piping that into the params object for getStaticPaths

Voilà! Now the site won't need to parse every blog post to render each of these preview pages! The static file will already have been generated and ready to go on request.

Floating Improv

☁️

The backing is prerecorded, but Miranda from the other room thought that I just got WAY better all of a sudden 😂

Sunset Flower

Lizalfos

Mitigating Content Layout Shift with Next Image Component

One aspect of developing my art grid was moving away from the Next image component and choosing a more flexible option with special css.

There are still plenty of spots on the site I wanted to keep using it, though! This week, I wanted to jot down why.

CLS

Content Layout Shift is something I've written about a few times. Surprisingly, this is my first touch on images, the largest culprits of creating CLS!

A page is typically peppered with images throughout. An image can be wholly optimized to be very lightweight, but can still contribute to a negative user experience if the dimensions are not accounted for.

Say you're reading this blog. And a put an image right above this paragraph. If an image FINALLY loads as you're reading this, all of a sudden this paragraph is pushed down and now you have to scroll to find your place. Ugh.

The Solution

The way to mitigate this is pretty simple: Set dimensions on your images.

Easy if you already know what they are: Use css to set explicit widths and heights. You can even use media queries to set them depending on the screen size.

It gets a little trickier if you're doing this dynamically, not knowing what dimensions your image will be. The best bet, then, is to set a container for the image to reside in , and have the image fill the container. Thinking of a div with an img child.

Next Image Component

It's not too involved to code this yourself, but Next.js comes out of the box with a component to handle this along with many other goodies. The Image Component in Next offers Size optimization for local images and lazy loading.

Here I'm using the component for my albums page

import React from 'react';

import Image from 'next/image';

import Link from 'next/link';

const MusicGrid = ({ albums }) => {

return (

<>

<section className="music_display">

{albums.map((album) => (

<article key={album.title}>

{/* <Link href={album.link}> */}

<Link href={`/${album.slug}`}>

<a data-test="musicGridLink">

<Image src={album.coverURL} width="245" height="245" />

<span>{album.title}</span>

</a>

</Link>

</article>

))}

</section>

</>

);

};

export default MusicGrid;And here is what's generated to the DOM. It's a huge sample, but you can find a few interesting points in there:

The key pieces being the srcset used for different sized images generated for free. These are made with externally sourced images, interestingly enough, but they're generated by the component to handle rendering specifically to the page!

<article>

<a data-test="musicGridLink" href="/forest"

><span

style="

box-sizing: border-box;

display: inline-block;

overflow: hidden;

width: initial;

height: initial;

background: none;

opacity: 1;

border: 0;

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

position: relative;

max-width: 100%;

"

><span

style="

box-sizing: border-box;

display: block;

width: initial;

height: initial;

background: none;

opacity: 1;

border: 0;

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

max-width: 100%;

"

><img

style="

display: block;

max-width: 100%;

width: initial;

height: initial;

background: none;

opacity: 1;

border: 0;

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

"

alt=""

aria-hidden="true"

src="data:image/svg+xml,%3csvg%20xmlns=%27http://www.w3.org/2000/svg%27%20version=%271.1%27%20width=%27245%27%20height=%27245%27/%3e" /></span

><img

src="/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fres.cloudinary.com%2Fcpadilla%2Fimage%2Fupload%2Ft_optimize%2Fchrisdpadilla%2Falbums%2Fforest.jpg&w=640&q=75"

decoding="async"

data-nimg="intrinsic"

style="

position: absolute;

top: 0;

left: 0;

bottom: 0;

right: 0;

box-sizing: border-box;

padding: 0;

border: none;

margin: auto;

display: block;

width: 0;

height: 0;

min-width: 100%;

max-width: 100%;

min-height: 100%;

max-height: 100%;

"

srcset="

/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fres.cloudinary.com%2Fcpadilla%2Fimage%2Fupload%2Ft_optimize%2Fchrisdpadilla%2Falbums%2Fforest.jpg&w=256&q=75 1x,

/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fres.cloudinary.com%2Fcpadilla%2Fimage%2Fupload%2Ft_optimize%2Fchrisdpadilla%2Falbums%2Fforest.jpg&w=640&q=75 2x

" /><noscript

><img

srcset="

/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fres.cloudinary.com%2Fcpadilla%2Fimage%2Fupload%2Ft_optimize%2Fchrisdpadilla%2Falbums%2Fforest.jpg&w=256&q=75 1x,

/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fres.cloudinary.com%2Fcpadilla%2Fimage%2Fupload%2Ft_optimize%2Fchrisdpadilla%2Falbums%2Fforest.jpg&w=640&q=75 2x

"

src="/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fres.cloudinary.com%2Fcpadilla%2Fimage%2Fupload%2Ft_optimize%2Fchrisdpadilla%2Falbums%2Fforest.jpg&w=640&q=75"

decoding="async"

data-nimg="intrinsic"

style="

position: absolute;

top: 0;

left: 0;

bottom: 0;

right: 0;

box-sizing: border-box;

padding: 0;

border: none;

margin: auto;

display: block;

width: 0;

height: 0;

min-width: 100%;

max-width: 100%;

min-height: 100%;

max-height: 100%;

"

loading="lazy" /></noscript></span

><span>Forest</span></a

>

</article>Swing Low

Sangin'! With Lucy!